In the studio: Olive Gill-Hille

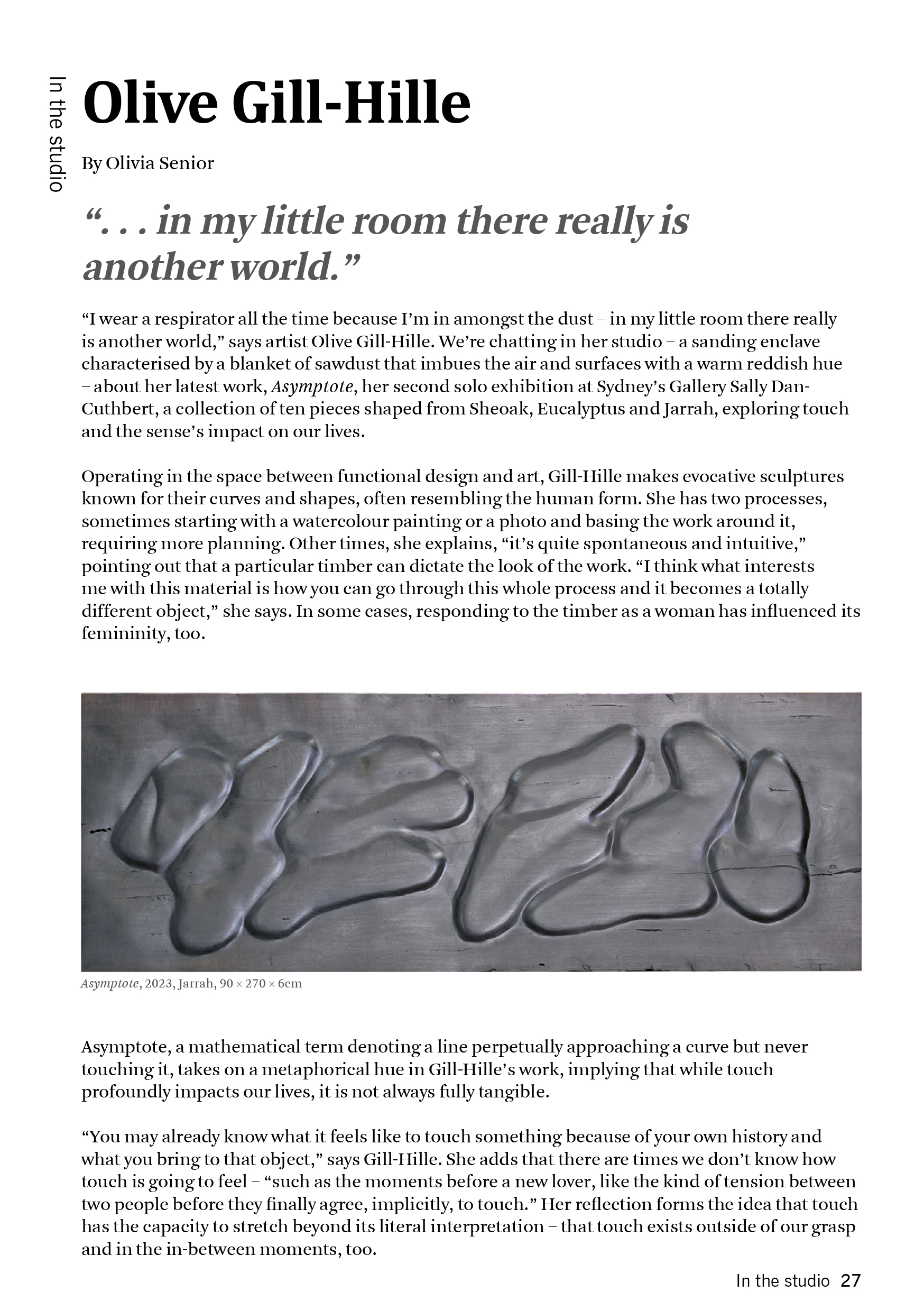

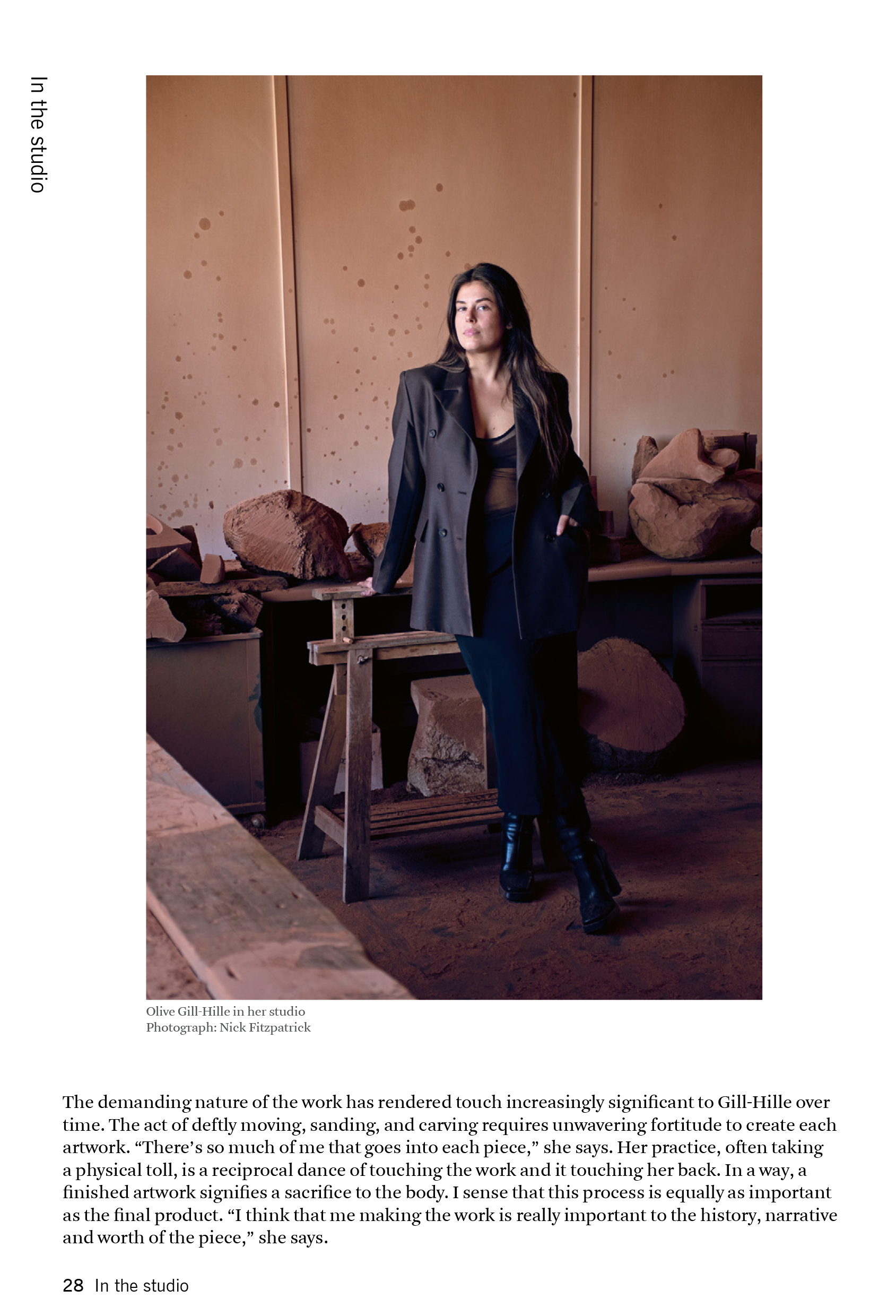

“I wear a respirator all the time because I’m in amongst the dust – in my little room there really is another world,” says artist Olive Gill-Hille. We’re chatting in her studio – a sanding enclave characterised by a blanket of sawdust that imbues the air and surfaces with a warm reddish hue – about her latest work, Asymptote, her second solo exhibition at Sydney’s Gallery Sally Dan- Cuthbert, a collection of ten pieces shaped from Sheoak, Eucalyptus and Jarrah, exploring touch and the sense’s impact on our lives.

Operating in the space between functional design and art, Gill-Hille makes evocative sculptures known for their curves and shapes, often resembling the human form. She has two processes, sometimes starting with a watercolour painting or a photo and basing the work around it, requiring more planning. Other times, she explains, “it’s quite spontaneous and intuitive,” pointing out that a particular timber can dictate the look of the work. “I think what interest me with this material is how you can go through this whole process and it becomes a totally different object,” she says. In some cases, responding to the timber as a woman has influenced its femininity, too.

Asymptote, a mathematical term denoting a line perpetually approaching a curve but never touching it, takes on a metaphorical hue in Gill-Hille’s work, implying that while touch profoundly impacts our lives, it is not always fully tangible.

“You may already know what it feels like to touch something because of your own history and what you bring to that object,” says Gill-Hille. She adds that there are times we don’t know how touch is going to feel – “such as the moments before a new lover, like the kind of tension between two people before they finally agree, implicitly, to touch.” Her reflection forms the idea that touch has the capacity to stretch beyond its literal interpretation – that touch exists outside of our grasp and in the in-between moments, too.

The demanding nature of the work has rendered touch increasingly significant to Gill-Hille over time. The act of deftly moving, sanding, and carving requires unwavering fortitude to create each artwork. “There’s so much of me that goes into each piece,” she says. Her practice, often takin a physical toll, is a reciprocal dance of touching the work and it touching her back. In a way, a finished artwork signifies a sacrifice to the body. I sense that this process is equally as important as the final product. “I think that me making the work is really important to the history, narrative and worth of the piece,” she says.

The more we talk, the clearer it becomes why the artist takes such an arduous approach to her practice and why touch echoes throughout her work. “My parents are both painters and it’s funny because my process does start with painting,” she says. “But in a roundabout way, I’ve rebelled from that because I see the world in three dimensions, and I want to create in that realm.” Most importantly, perhaps, Gill-Hille’s art transforms natural elements into sculptures, adding depth and context to their stories, existing to touch lives along the way. “I see its next life as being the art object in someone’s home, and however they treat it, is its next story.”

This article was originally published in the January issue of the monthly magazine Art Almanac. Photography by Nick Fitzpatrick and curtesy of the artist. You can also find the article online.